Joel Mitchell and Katy Jordan

As mentioned in Chapter 1, EdTech Hub undertook a series of rapid evidence reviews (RERs) in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. The RER format is a pragmatic compromise between the rigour of a systematic review and the speed of response demanded by a crisis situation. The EdTech Hub RER approach drew on the Cochrane Rapid Review guidance (Garritty et al., 2020) — adapting it to be more applicable to education research in the current context of needing to disseminate key lessons from existing evidence to inform policy and practice. In order to do this, the search criteria were focused and queried key databases relevant to education and technology. Strict screening criteria were applied to limit time wasted on marginally relevant literature. In order to equitably represent sources from a broader range of relevant research, the RERs also included intervention-related research and limited emphasis on aggregated findings, meta-analysis, and systematic reviews. This helped to ensure that the reviews included practical findings, with the intended audience being policymakers and individuals involved in educational decision-making across systems.

The research process therefore comprised a systematic sequence of scoping, searching, and screening. In the scoping phase, the research questions and eligibility criteria were defined and initial searches were conducted to help elicit relevant search terms for the search queries. A focused set of searches was then run within the relevant academic databases. The search results were then screened according to the inclusion criteria and the final set of studies were analysed thematically. While the RERs were completed concurrently by different teams, a consolidated approach to review and quality assurance ensured a consistent approach despite the different themes.

Scoping research

The methodological approach is informed by the Cochrane Collaboration Rapid Reviews Methods Group interim guidance on producing rapid reviews (Garritty et al., 2020). This guidance has subsequently been developed further and published by the group (Garritty et al., 2021). Systematic reviews are often regarded as sitting atop the hierarchy of standards of evidence (Cochrane Collaboration, 2019); Higgins and Green (2011) distinguish a systematic review thus:

“A systematic review is secondary research that seeks to collate all primary studies that fit prespecified eligibility criteria in order to address a specific research question, aiming to minimise bias by using and documenting explicit, systematic methods.”

However, a full systematic review approach is a substantial research undertaking, and RERs are intended to quickly provide an overview of the research landscape around a particular topic of current interest. The approach is similar to scoping studies, which have characteristics in common with systematic reviews; both involve taking a logical, rigorous approach to searching and synthesis across the research literature (Colquhoun, et al., 2014; Pham, et al., 2014). However, scoping reviews differ from systematic reviews in that the goal is typically to profile the current status of a field and identify gaps rather than evaluate the evidence in relation to a specific, bounded question (Arksey, & O’Malley, 2005). As such, this approach to literature discovery is widely considered as representing a stage prior to a systematic review where the key concepts and ideas that define a field are explored and discovered in an iterative process (Daudt et al., 2013; Levac et al., 2010).

Scoping studies follow a similar protocol and are explicit in documenting the process of literature searching, screening, and the reasons why studies have been selected for inclusion. The scoping process for the RERs began by noting relevant keywords and terms already known to the authors to search for additional literature. The process was iterative, with the terms found in one article leading to searches for other articles that then revealed different or the same terms.

The search terms used for individual RERs are shown in full in the Annex. It is important to draw attention to the point that when a search term identified an article with a relevant title, that article was saved to be screened later alongside others that were found during the main literature search, as explained below.

Literature searches

The literature search began after the search terms had been established at the end of the scoping research. Google Scholar constituted the primary bibliographic database for literature, with additional searches being undertaken using Scopus and EdTech Hub’s internal searchable publications database (‘SPUD’). Details of the particular databases used can be found in each of the RERs. While Google Scholar proved beneficial in aiding discovery of literature aggregated from many sources, including less established portals and publishers, this also had the side effect of surfacing a number of low-quality papers, despite having relevant titles and abstracts. Therefore, these were only filtered out after the full text had been read.

We would also draw your attention to the other methods that were used to find literature. While the main thrust of the literature review involved a highly systematic approach, we recognised that there might be influential literature that might not be captured through those searches alone. Therefore, for some of the RERs, the authors decided to search the reference lists of the most relevant papers found through the systematic literature review for additional sources (a process known as ‘snowball sampling’). Expert recommendations were also used. The database searches were typically supplemented by additional searches of non-academic, informal, and grey literature to identify examples of emerging practice.

It is important to note that the results were not screened and ranked for quality or limited to peer-reviewed academic publications. Relying solely on peer-reviewed academic articles would have resulted in a narrower review. Crucially, this would also have excluded a larger number of voices from LMICs due to the systemic factors that exclude many academic researchers in LMICs from mainstream peer-reviewed journals (Czerniwicz, 2016).

Screening and eligibility criteria

The title and abstract screening, as well as all other subsequent screenings, were conducted according to predefined eligibility criteria, which are shown in full for each RER in the Annex.

In some cases, where few studies were found, a small, complementary collection of sources that were deemed especially informative but did not meet all criteria, were also included. An exception, for example, might therefore be made if a study explored the use of technology for refugee education but focused on refugee camps in high-income countries.

Following database searches, the literature discovered was then subject to a screening process, similar to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol (Liberati et al., 2009). This comprised the following steps, with the number of records being included and excluded recorded at each step:

- All studies yielded from literature searches are screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria at the level of title and abstract.

- Duplicate studies are removed.

- Remaining studies are screened according to the criteria but are now applied at the full document text level.

- Any extra documents that have been uncovered by snowball sampling or through recommendations, which meet the criteria for inclusion, are added.

- The final set of studies then form the sample for thematic analysis.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to each RER, and the number of studies screened, are shown in full in the Annex.

Limitations

While the RER methodology represents a rigorous and transparent approach to reviewing the research literature and is based on elements of systematic reviews, it is also subject to limitations stemming from the rapid timeframe and the nature of available evidence. These include the following.

Limited availability of data

There is an acknowledged and long-standing gap in the evidence base on EdTech and the focal topics. For example, gaps are noted in relation to refugee education and emergency settings, particularly in terms of rigorous evaluations, impact studies, and the perspectives of refugee communities and children (see Chapter 5 for further discussion). There are notable gaps in other settings, particularly those affected by disasters and epidemics. Furthermore, for several of the topics, it was found that existing evidence tended to focus more frequently on Higher Education (HE) rather than school-age learners and systems, and since HE research was out of scope, there was limited evidence.

The search and inclusion strategy

An inherent limitation of the RER is that the search and inclusion strategy is not, by design, exhaustive, and therefore it is possible that not all relevant literature has been located and included. Further, the searches were conducted in English, meaning that relevant literature in languages other than English that are spoken across many LMICs largely remain unacknowledged.

Quality of the evidence

The evidence identified within the literature across the RERs varies in terms of quality and robustness. While some projects have been well-evaluated and frequently cited across the literature, evidence on others is only briefly referenced or studied as part of a smaller evaluation or research project. Variable quality also prevented rigorous comparative analysis from being drawn and instead reviews tended to be more descriptive in nature. Quality was not assessed as part of the screening criteria, in order to ensure that as wide and inclusive a range of relevant studies were included.

The generalisability of the findings to the context of the Covid-19 pandemic

While the purpose for undertaking the RERs was to be able to inform responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, the existing studies were undertaken in a different context and findings will not necessarily transfer easily to the current crisis.

The positionality of the authors

The scope of EdTech Hub focuses on the use of technology in education in LMICs; however, it must be acknowledged that it is primarily led and funded by organisations based in high-income countries. Although effort is placed into trying to best represent and centre the needs and experiences of children from LMICs, there are limitations in doing so as mainly UK-based researchers.

The evidence landscape

The main purpose of the RERs was to provide evidence-based guidance during the Covid-19 pandemic and the educational disruption this has caused (and continues to cause). Additionally, taken together, the RERs also provide an interesting (albeit incomplete) view across the research literature associated with EdTech in LMICs. Given that ‘EdTech’ is an umbrella term, and the broad range of countries that are defined as LMICs, it would be extremely difficult to conduct an exhaustive literature review covering EdTech in LMICs as a whole. In combination, the collection of RERs and the research that they draw upon, provide a partial overview of EdTech in LMICs. Similar search strategies and screening processes were used across the RERs. The number of articles selected for inclusion varied according to topic, from 24 to 95.

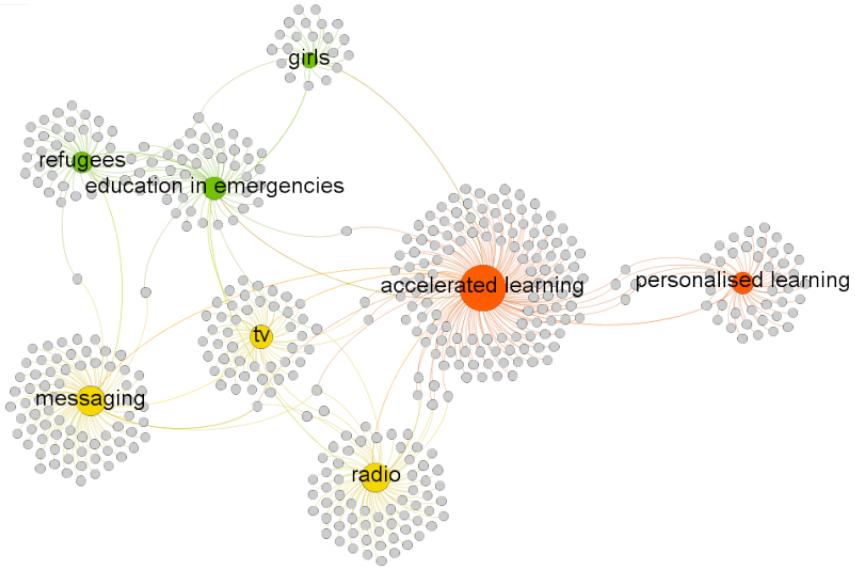

In addition to providing an indication of the relative size of literature bases associated with the respective topics and EdTech in LMICs, the collection of articles cited within the RERs can also be explored in terms of how much overlap exists between the topics. Figure 2 shows a citation network, where grey nodes represent articles, and coloured nodes represent RERs. A link between a grey and coloured node represents the articles’ citations within an RER. Node size is scaled according to the number of works cited within each RER. A total of 448 unique articles were cited in the RERs (including six frequently-cited methodological articles). The layout of the network in Figure 2 illustrates the extent of overlap between the topics of the eight RERs and highlights how the topics align with each other. The groups that emerged form the basis of the three sections within this volume.

The articles that form the connections between different RERs would be a valuable starting point for reading lists around EdTech in LMICs. Five of the connected papers relate specifically to EdTech responses to the Covid-19 pandemic (Azevedo et al., 2020; Education Endowment Foundation, 2020; Hallgarten et al., 2020; Vegas, 2020; World Bank, 2020).

The two most closely related RERs are education in emergencies and refugee education, as two closely linked topics, with seven articles in common. The decision was taken early on to separate out these two RERs because initial searches suggested the study would have to cover too much material. A specific concern was that the two studies should distinguish sufficiently between immediate emergency-response interventions, as opposed to protracted disruptions to education. The importance of this distinction has only become clearer as the pandemic has continued to disrupt education. Most of the co-cited articles in the RER on refugees and education in emergencies are reviews themselves, which together would form essential further reading for the reader interested in these topics (Burde et al., 2015; Carlson, 2013; Gladwell & Tanner, 2014; Lewis & Thacker, 2016; Tauson & Stannard, 2018; Unwin et al., 2017). A further review, by Dahya (2016), spans the topics of education in emergencies, refugee education, and girls’ education. A recent study by Almasri et al. (2019) provides a practical example of developing a digital platform to support education for refugees and children affected by the recent crisis in Syria.

As the two reviews concerned primarily with approaches to the use of EdTech, three papers link the RERs on accelerated learning and personalised learning. Examples include the learning gains in mathematics associated with computer-assisted learning interventions in India (Banerjee et al., 2007) and Nigeria (Gambari et al., 2016), while Zaulkerman et al. (2013) draw on the example of using an artificial intelligence tutor in Pakistan, to discuss key considerations for contextualising this type of technology. Menendez et al. (2016) form a connection between accelerated learning and education in emergencies, through their review focusing specifically on accelerated education programmes during crises.

The RER on accelerated learning also shares common ground with one of the technology-focused reviews, specifically radio (Aderinoye et al., 2007; Anzalone & Bosch, 2005; Bosch, 2004; Potter & Naidoo, 2009) and to a lesser extent television (Borzekowski et al., 2019; Moland, 2019). Apart from an older connection related to distance education in low-income contexts more broadly (Perraton, 2005), cited in both the radio and television reviews, there are few citation links between the cluster of RERs focused on particular technologies. Technologies linked to particular contexts include a link between messaging apps and refugee education, via a study by Dahya et al. (2019) focused on the use of messaging apps to support teachers in refugee camps, and a link between education in emergencies and radio through an example in Sierra Leone (Barnett et al., 2018).

As part of EdTech Hub’s commitment to openness and knowledge sharing, the literature cited by each RER has been added to the EdTech Hub Evidence Library, which is an online bibliographic database maintained and curated by EdTech Hub. The Evidence Library can be accessed publicly at: https://docs.edtechhub.org/lib/.